Sobre el fracaso / 2010

Accompanying the main drawings, an independent editorial product appears that compiles the biographies of those characters and at the same time includes collaborative texts from artist-writers, delving freely and individually into the concept that the entire work proposes.

In the publication there are texts by: Andrés Felipe Uribe, Alma Sarmiento, Victor Albarracín, Fernando Escobar, Humberto Junca, Alfonso Pérez, Natalia Ávila, Selnich Vivas, Juan Mejia, Gabriel Mejía, Énrique Lozano and Manuel Kalmanovich.

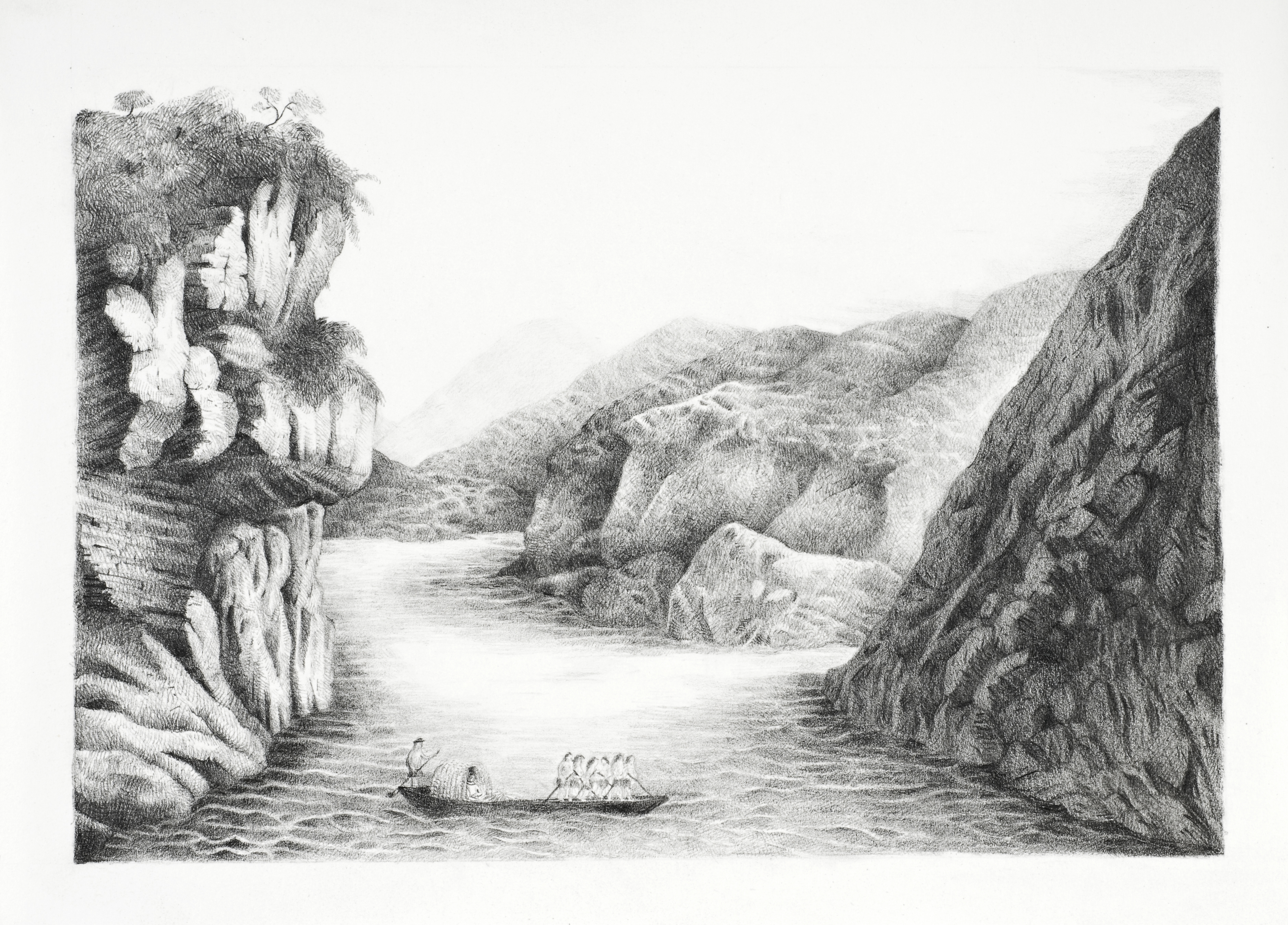

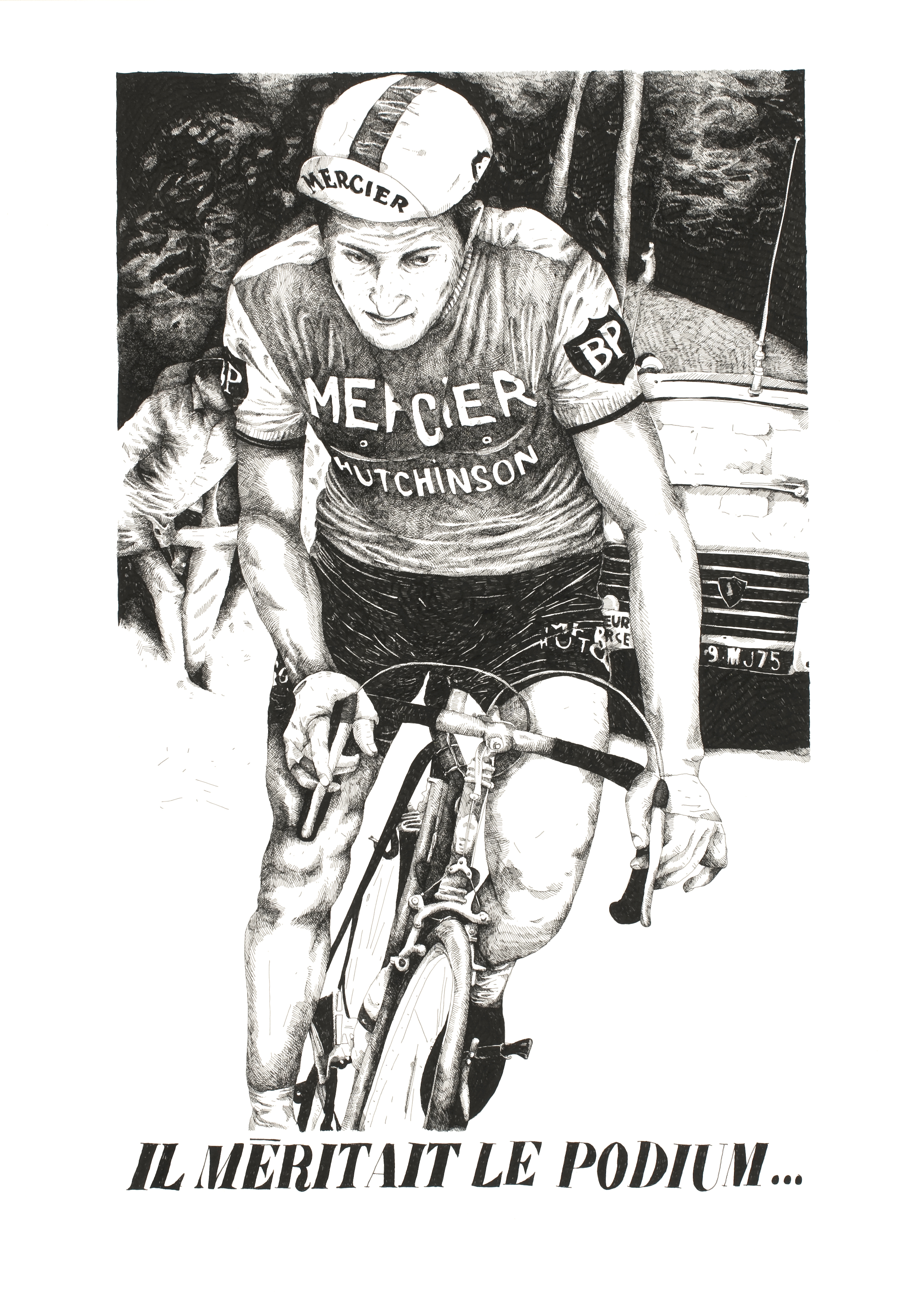

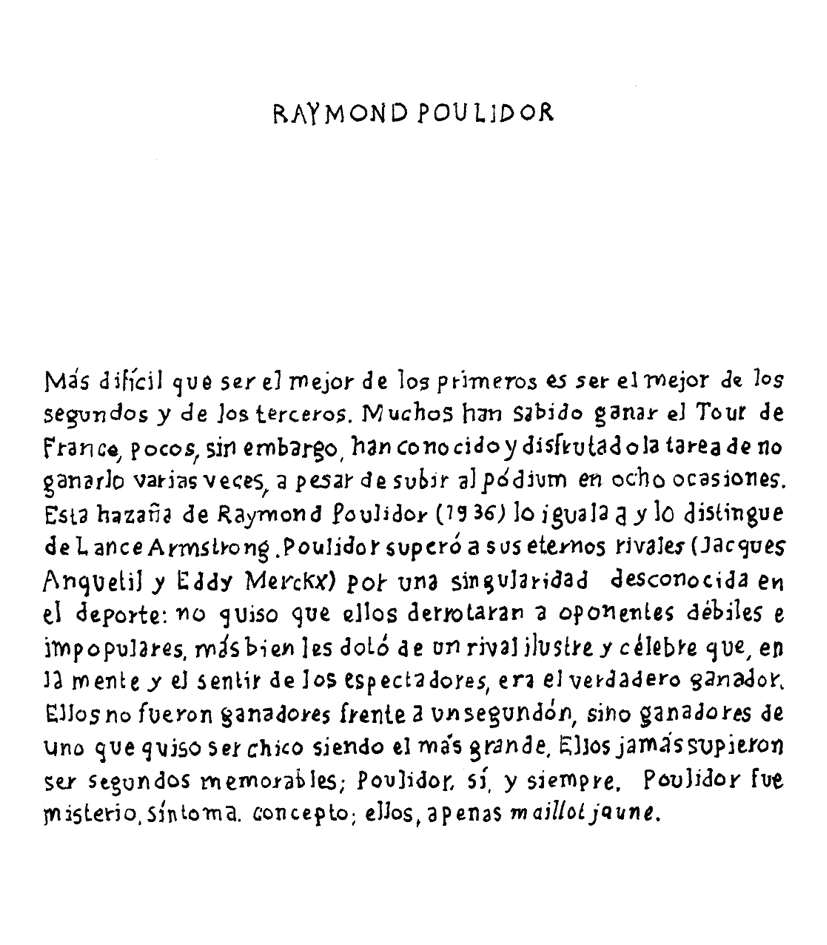

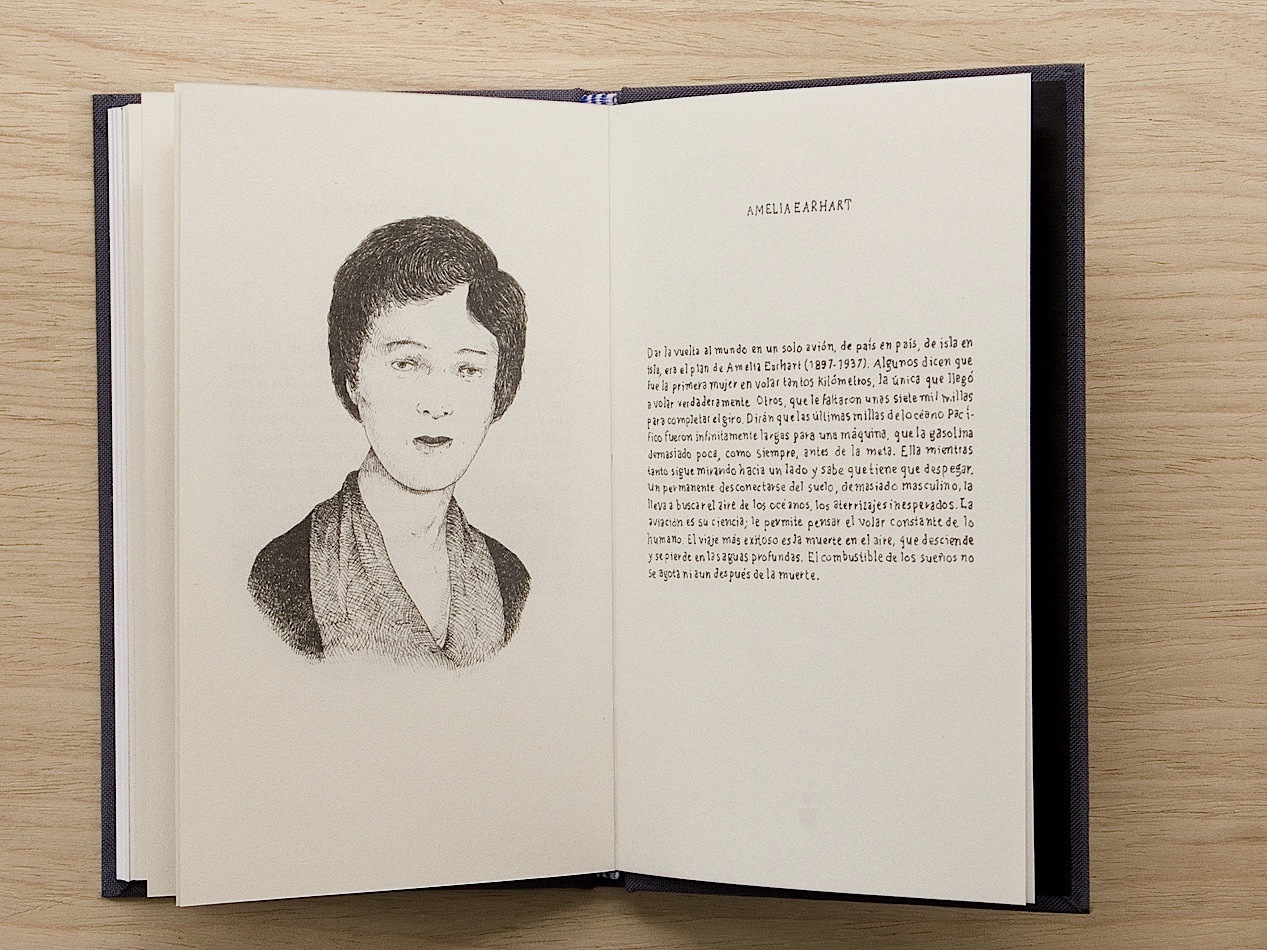

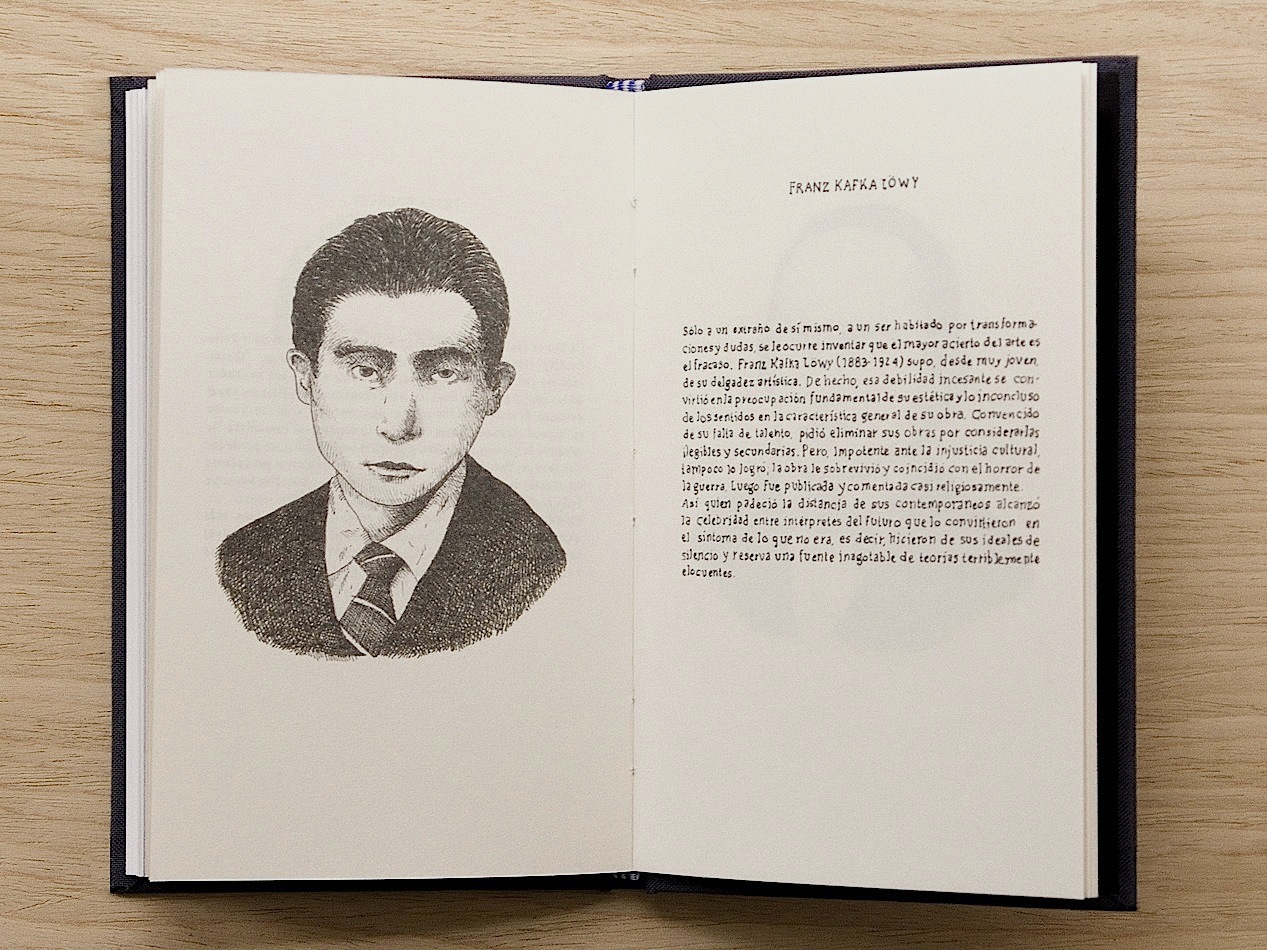

I recently read Robert Venturi, the architect, and in the midst of his reflections I came across adefinition of art. He says that he recognizes art in the design of a city or in a building because ofthe validity of the questions it poses and the liveliness of meaning. This strong maxim serves fora writing about failure, an exhibition that before all else raises a valid question, a questionabout a feeling that is part of the painful sentimental education to which we have beensubjected and the naive belief that Man is a hero who must master chaos.Similar to Venturi, the exhibition raises a valid question and a very lively relationship withmeaning since it explores different examples of possible failures. Crucially, the stories show thatthis is a debatable concept: Raymond Poulidor came in second eight times in the Tour deFrance, Robert Falcon Scott had a "second" adventure to the South Pole, and Peter Buckley was the eternal loser in boxing. Of the many who have died in the attempt, Kevin Mancera chosestwo "high flyers": Amelia Earhart and Adelir de Carli, the latter of whom was lost in a flyingapparatus that used helium balloons. Examples of eternal tenacity include William Miller andhis predictions about the second coming of Christ and that of Lope de Aguirre and his endlessmisery. A great show of tenacity that comes from an overwhelming desire, and which weshould imitate, is seen in Florence Foster Jenkins who, in spite of her discordant voice and theridicule it brought her, dedicated her life to singing. I recall the seemingly terrible failure ofManuel Quintin Lame and his struggle to return the land to the Indians. I couldn’t forget thestory of the poor rich girl, Christina Onassis, and the presidential candidates of Colombia, suchas Gabriel Arturo Goyeneche and his exotic projects. I find examples of failures that are suchaccording to perspective, like Franz Kafka, who despite his doubts about the relevance of hiswritings, became, both himself and his work, a success.

The exhibition is in itself a motive for drawing, but Mancera is concerned with structuring thisskill within a plan, a theme, and also inscribing it within an encyclopedic interest. The companyof Diderot and D'alambert in the eighteenth century seems necessary today in the sense of'liberating' words from their conventional meanings and looking for other definitions. For theexhibition, Mancera relies on portraits from an encyclopedia, a newspaper or the net, drawnwith pen or pencil. The exhibition reminds me of the portraits of German artist Gerhard Richter.I refer to his paintings of characters with unknown names, that (if one takes the trouble to findout) represent Nobel Prizewinners in chemistry, economics and physics, names of unknownresearchers whose discoveries have been fundamental to everyday life. It also reminds me ofthe portraits of a bearded Juan Mejia, the Colombian artist; a line up of drawings of charactersapparently chosen only for their beard, and in the midst of the better known names such asFreud or Marx, writers unknown to many such as Georges Perec and Raúl Gómez Jattin arefound.

Why has drawing become so effective after the rule of photography and video? I don’t know. Iwould venture to say that it is valid according to the subject. Perhaps drawing for drawing’s sake still instills in me a bit of laziness, with all due respect to draughtsmen; it stimulatesastonishment at the skill, which to me does not seem enough alone for art. The theme of failuretreated in drawing is another thing: it records an educational absurdity that we have sufferedand that we have to discuss. It takes us back in order to revisit and emphasize - with little lines -the desires of others who possess only the meaning or the nonsense of their own desires.

While this exhibition seeks to influence the definitions we have for things and to free them, italso presents a contemporary dilemma between image and text and their coexistence orstruggle. In this exhibition, portraits and written histories are inseparable and coexist on thewall without any importance being given to one or the other. The image returns us toschoolbooks, to encyclopedias, to the newspaper, to the gesture, to the place of origin of theportrait, to sharpness, to the detail of a dress and the details of things, to textures and distantplanes. The texts lead us to the horror of school with its castration of ideas, a world ofdiagnostics, ambiguities, social and collective psychology. To the world of the paradox betweenresult and process, between desire and paralysis, between order and chaos. The text takes usto our own world. That's why I like exhibitions that end up in me and not in the gallery. Theseexhibitions leave me thinking about my problems or those of others; they are not only areflection on form. Upon leaving this exhibition, I keep thinking about failure; I cannot define it,but what a delight it is to send the need for success on vacation!

Natalia Gutiérrez, ArtNexus.